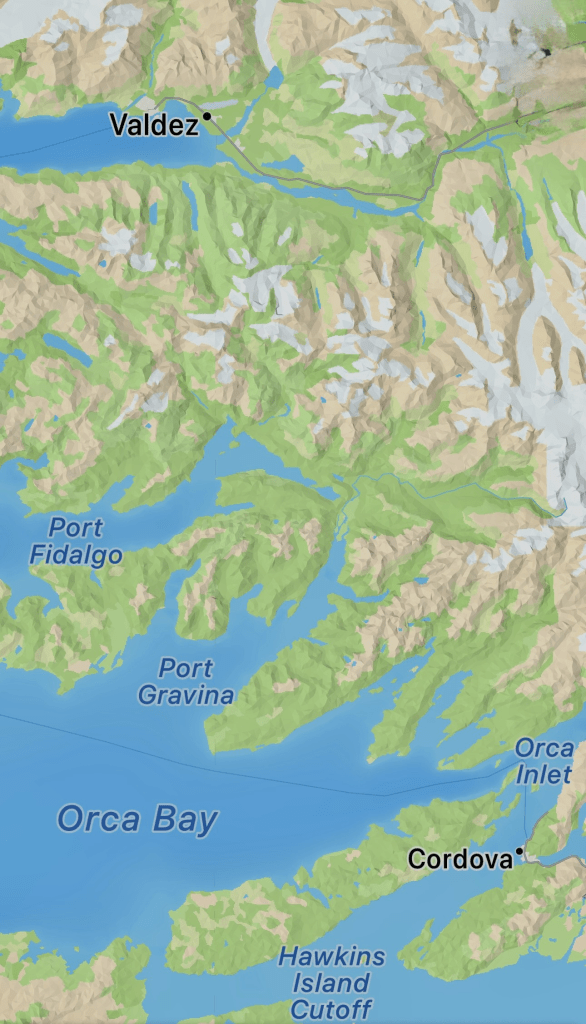

Valdez is another beautiful place with interesting history. It was named in the late 1700s after a Spanish Naval Officer, Antonio Valdez y Fernandez Bazan, by a Spanish explorer, Salvador Fidalgo. In 1790, during the Spanish expeditions in the Pacific Northwest, Fidalgo sailed into Prince William Sound & the Cook Inlet before anchoring in Cordova, Alaska (not too far from Valdez). Here, there was no Russian influence as there was in other parts of Alaska, and the Spanish explorers engaged in trading with the Indigenous people of the area including in and near the waters of the Orca Inlet. During this time, Fidalgo claimed Spanish sovereignty here and further up the coast to Valdez (named then “Puerto Valdes” in honor of the Spanish Naval officer above). Spain later relinquished land claims to the US north of the 42nd parallel.

**********************************

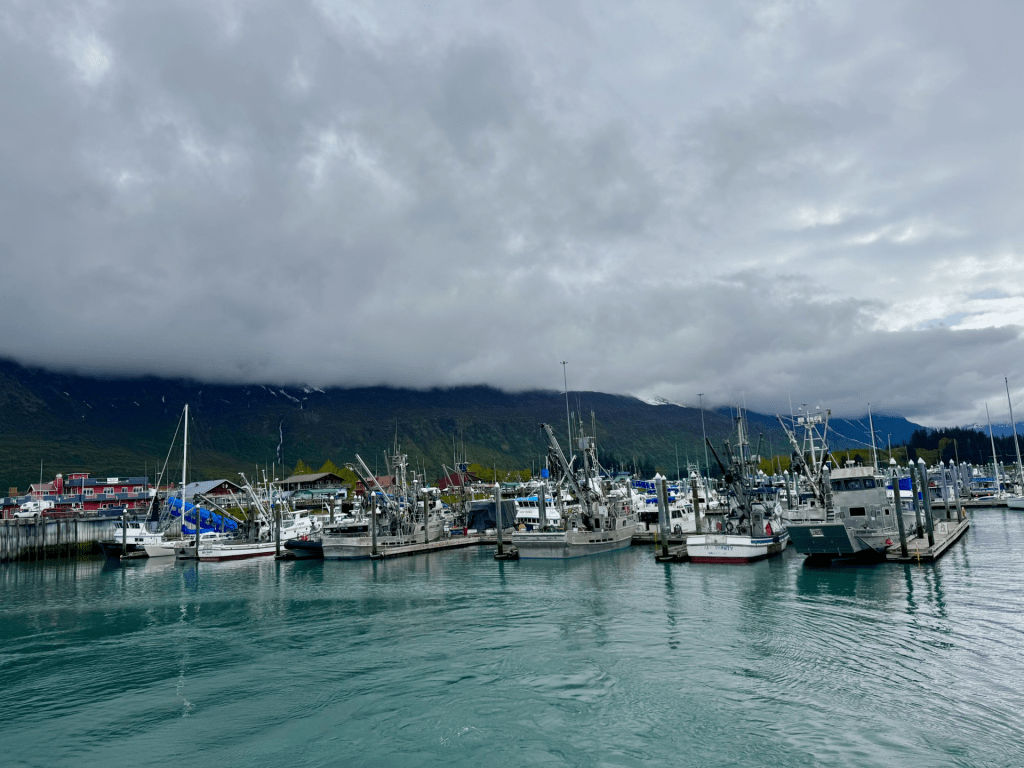

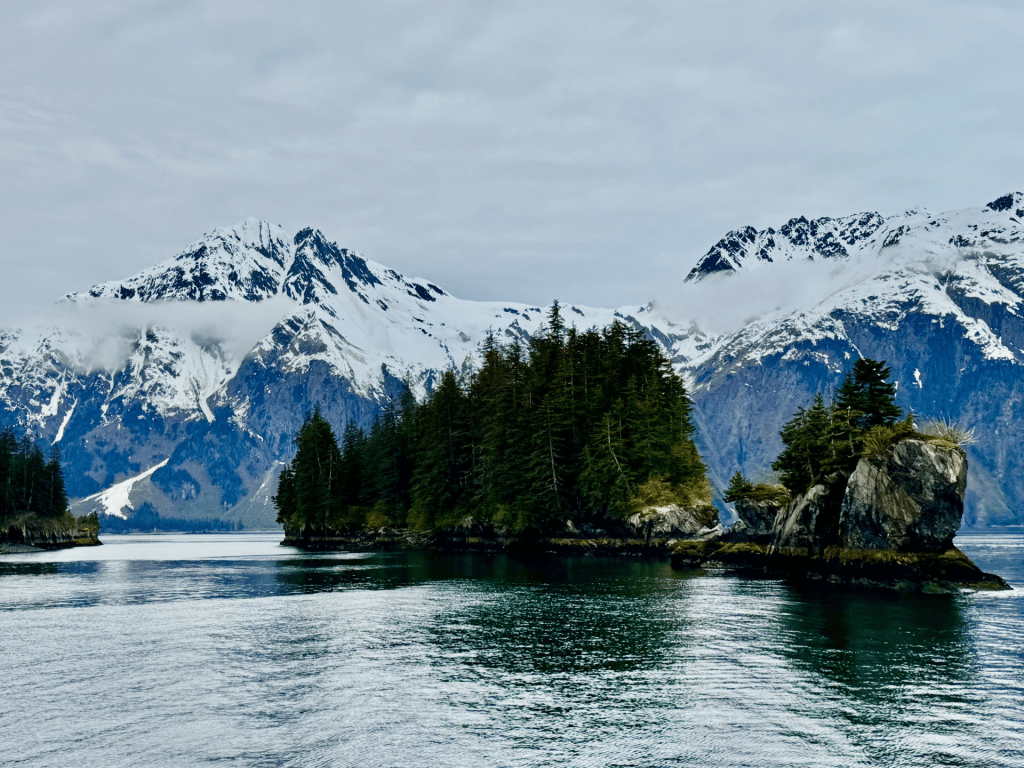

Valdez is at the head of a deep, beautiful fjord in the Prince WIlliam Sound surrounded by the heavily glaciated Chugach Mountains and is the northernmost port in North America that remains ice-free all year long. Its only road access is through the Thompson Pass and Keystone Canyon on the Richardson Highway which dead ends in Valdez. The waters of the Valdez Arm of the Prince William Sound become Port Valdez and deeper into the fjord is the town located near the fjord’s terminus.

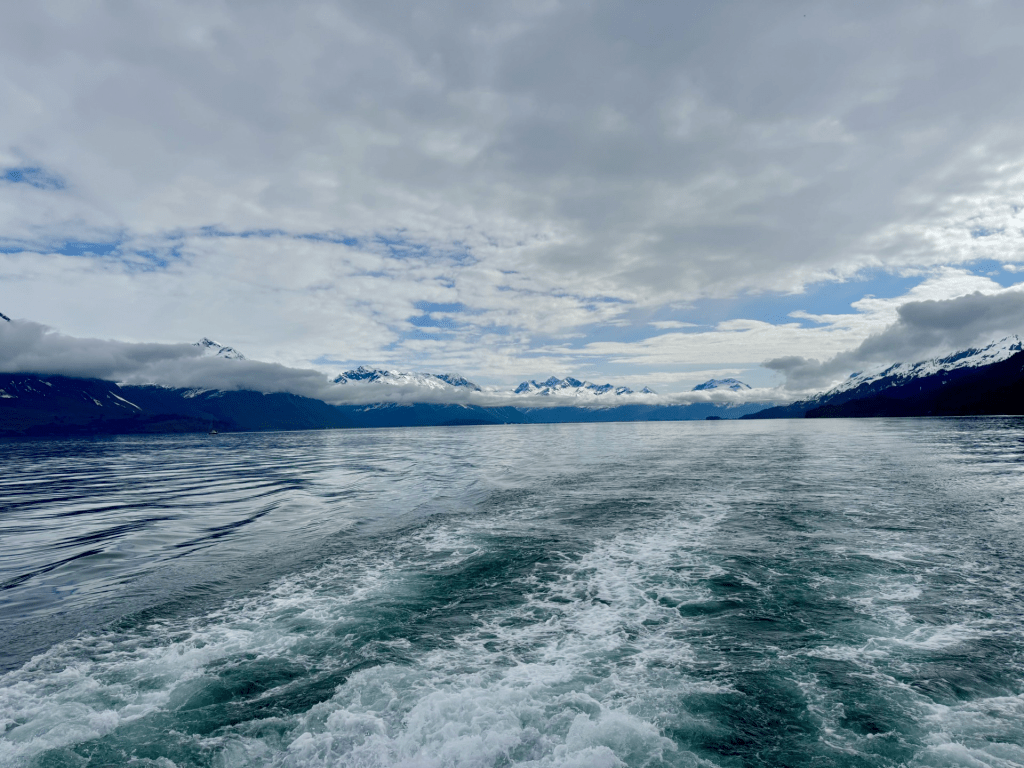

Below: taken from Port Valdez & the Valdez Arm of the Prince William Sound

The striations in the pics above and below are a plethora of marine invertebrates including mussels, barnacles, littorines (sea snails), along with plant life, such as seaweed and rockweed encrusted rocks, that line the rocky up rises from the water’s surface in the fjord.

Both marine flora and invertebrate fauna abound here. The black stripe just above the water surface pictured above are oodles of mussels that attach themselves to the rock substrate using strong, protein-based fibers, called byssal threads or byssus, that act like an strong adhesive and allow them to cling to surfaces even in challenging conditions such as the wave-pounded intertidal zones found in many coastal fjords in Alaska.

Pics above and below are scenes from the Valdez Arm

Although the winters in Valdez are much warmer than in most similar subarctic climates, they are colder and harsher than the milder climates of Kodiak and Cordova. Valdez gets an average annual snow fall of over 300 inches, with an annual rainfall of approximately 70 inches.

The town was formally incorporated in 1901, and since has been relocated from the east to the north side of Port Valdez after the 1964 Good Friday Earthquake. After the quake, the residents of Valdez remained for another three years as new construction on more stable ground was completed. During this time, 54 new structures (home and buildings) were trucked in resulting in the new, relocated town (only about 4 miles from the original) in its present location. The original town was eventually dismantled and any remains burned.

For those who don’t know of this massive quake, this was 9.3 in magnitude, occurring in the late evening on March 27, 1964, resulting in multiple tsunamis and 139 deaths. It was the most powerful earthquake ever recorded in North American history, and the second most in the world (since seismography was invented anyway……to be fair). There were 600 miles of fault line that ruptured after an estimated 500 years of stress build up resulting in earth fissures, landslides, and soil liquefaction with subsequent utter devastation to many Alaskan communities with damage and/or tsunamis as far as Anchorage, Seward, Kodiak and Whittier (among other towns in Alaska, British Columbia and as far away as Hawaii and Japan).

Some interesting history tidbits: the Richardson Highway; a gold rush scam; and railroad that never made it

~ It was not until the completion of the Richardson Highway in 1910 that the town of Valdez really began to thrive. The Richardson Highway created a connection between Fairbanks and Valdez, making Valdez the first overland supply route into Alaska’s interior. Initially, the highway was only open in summer months and in 1950 the route was opened year-round.

~ Before the creation of the Richardson Highway, there was a scam to lure prospectors to the area promoting use of the Valdez Glacier Trail instead of the Klondike Gold Rush trail to get to the Klondike Gold fields. This scam resulted in many more of the prospectors becoming ill with scurvy (severe vitamin C deficiency causing illness) and dying from the treacherous conditions (Valdez Glacier Trail was steeper and much longer) of this alternative trail.

~ Any hopes of Valdez having a railroad connection from the coast to Kennicott Copper Mine (near present day McCarthy, AK) were lost in 1907 during a shootout between rival rail companies. The Kennicott Copper Mine, located deep in the Wrangell-St Elias Mountains and near the infamous Copper River, had one of the richest copper ore deposits in North America, and had the railroad been completed, this would have been a vital link from Valdez to the mine. Instead, a rail line was created from Cordova to the mine, establishing a route from the coast to the interior. Today, near the Valdez side of the southern entrance into Keystone Canyon, you see the half-finished tunnel signifying the end of Valdez’s potential rail days.

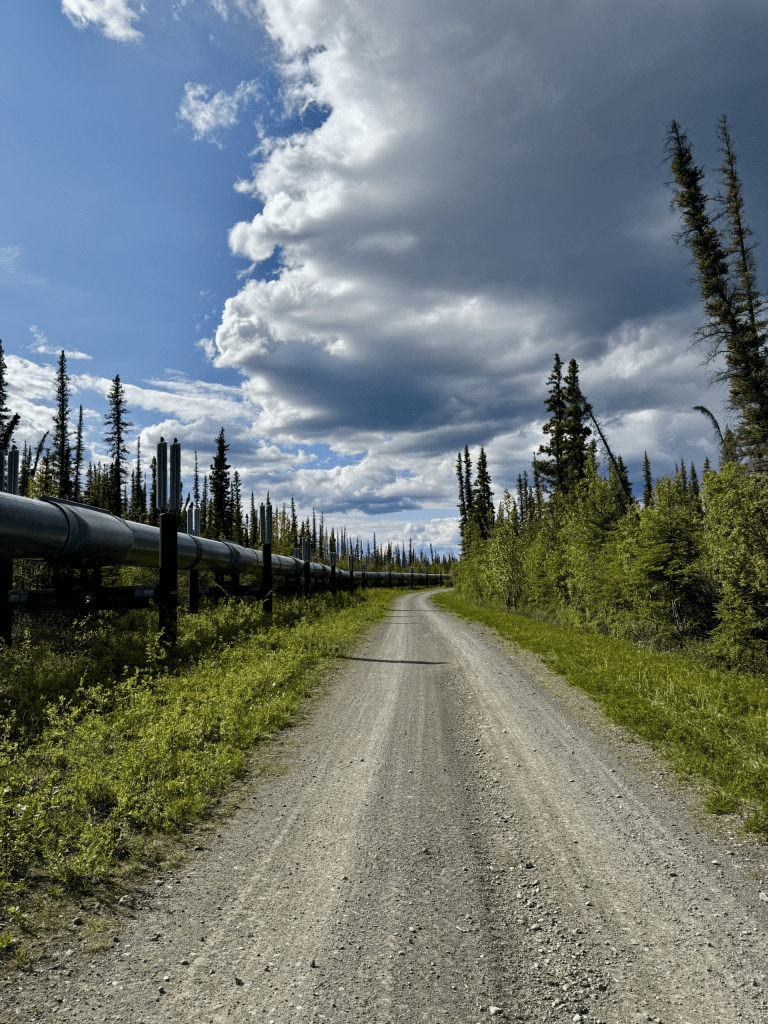

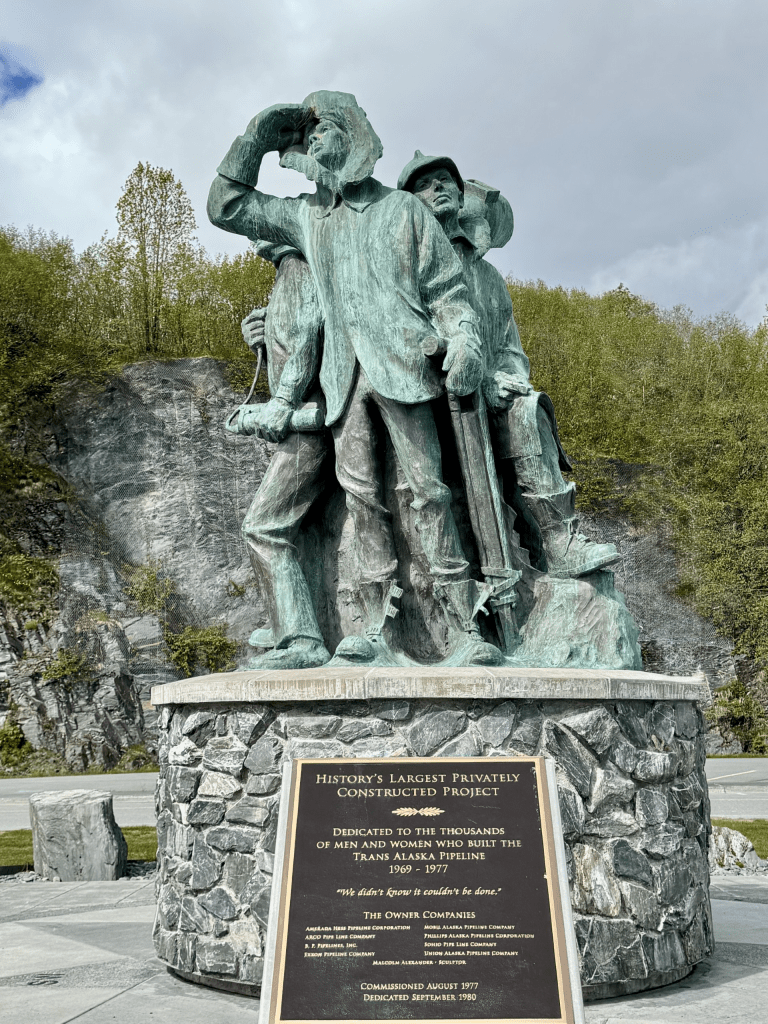

The Trans-Alaskan Pipeline

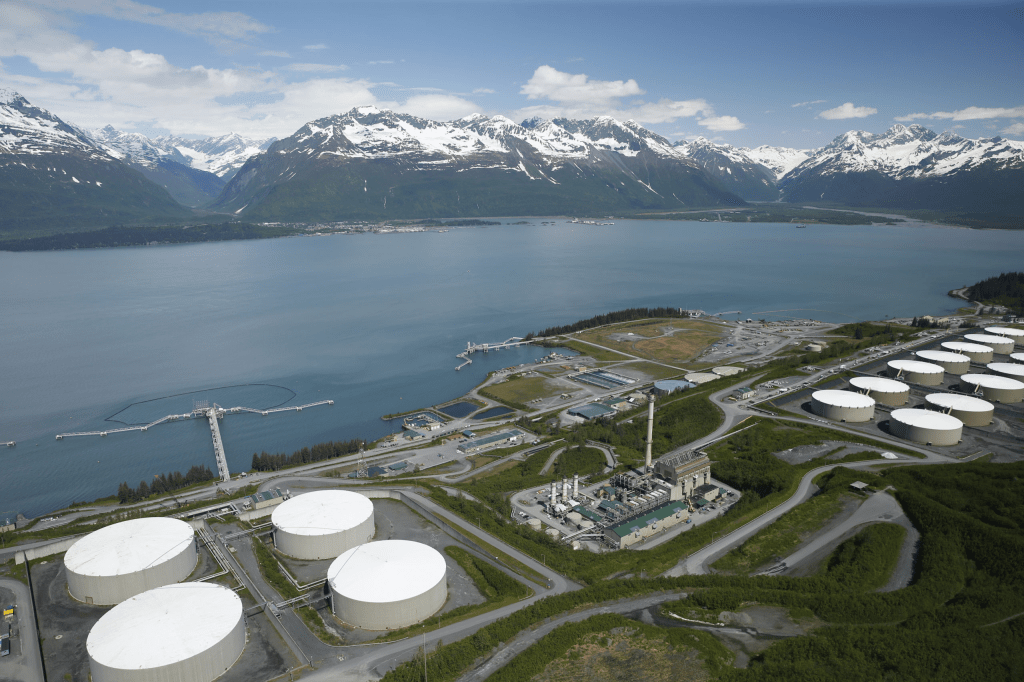

Ya can’t have a blog post about Valdez without mentioning the Trans-Alaskan Pipeline. This is where the pipeline ends after a long stretch (800 miles) from northern Alaska in Prudhoe Bay. The pipeline was built to transport oil from the Prudhoe Bay oil fields on Alaska’s northern slope to Valdez where it can be loaded onto tankers for further maritime transport. This obviously shaped then and now the Valdez infrastructure and boosting the local economy. The Valdez Marine Terminal in Valdez is an oil port and the departure point for the famous Exxon Valdez, the oil supertanker that struck a reef 6 miles west of Tatitlek, Alaska (approximately 25 miles from the town of Valdez), in the Prince William Sound where >10 million gallons of crude oil devastated the pristine ecosystem.

From a Native American perspective: The pipeline travels over many miles of Indigenous people’s land from various tribes, but none of the tribes associated with the land have ever received any monetary compensation or otherwise for this.

The Ahtna tribe are Alaskan Native Athabascan peoples (also called “Copper Indians”) with lands in the Copper River basin and the surrounding areas where a large portion of the pipeline is located. 197 miles of the pipeline traverses Ahtna lands but they have never received a penny for any of the 18 billion barrels of oil that have travelled through this pipeline. The Ahtna people are connected deeply to the land as well as the Copper River, with traditions steeped in a nomadic lifestyle relying on fishing, hunting and gathering in these areas for sustenance. Their culture encompasses a strong connection with their ancestral lands where cultural sites are still marked to reflect their traditions and history.

For the Ahtna people, not being invited to the table with regard to large projects such as the trans Alaskan pipeline has had damaging effects. The lack of compensation for the pipeline traversing their lands represents financial injustice as well as cultural, social and environmental impacts on this tribe via disrupting their way of life and ability to thrive on the land. Securing fair compensation and safeguarding the land mitigates this damage. Although there is now more inclusion of the native people in the development of these lands, disparities still exist.

Conversely, native communities have prospered in many ways from the development of various regions here – healthcare services, along with the development of relationships between corporations (including oil corporations) and Indigenous tribes have resulted in many services that otherwise would not be possible. This coupling between Alaska Native American tribes and various corporations have resulted in incredible financial assets for the Native people here that is unique to Alaska Natives when compared to Indian Services and tribal organization and politics (including allocation of resources) in the lower 48.

Currently, the Valdez terminal has 14 crude oil tanks for oil storage with 3-5 tankers leaving the terminal weekly. Since 1976, when the pipeline became operational, there have been over 19,000 full oil tankers that have departed this terminal.

Today, the Alyeska Pipeline Service Company is one of the largest Valdez employers (see following pic below)

Photo credit above of Valdez Marine Terminal taken from Alyeska Pipeline Website

***************************************

In addition to the oil industry, Valdez is also an access point for freight and goods to move from Valdez from ships and boats into Alaska’s interior.

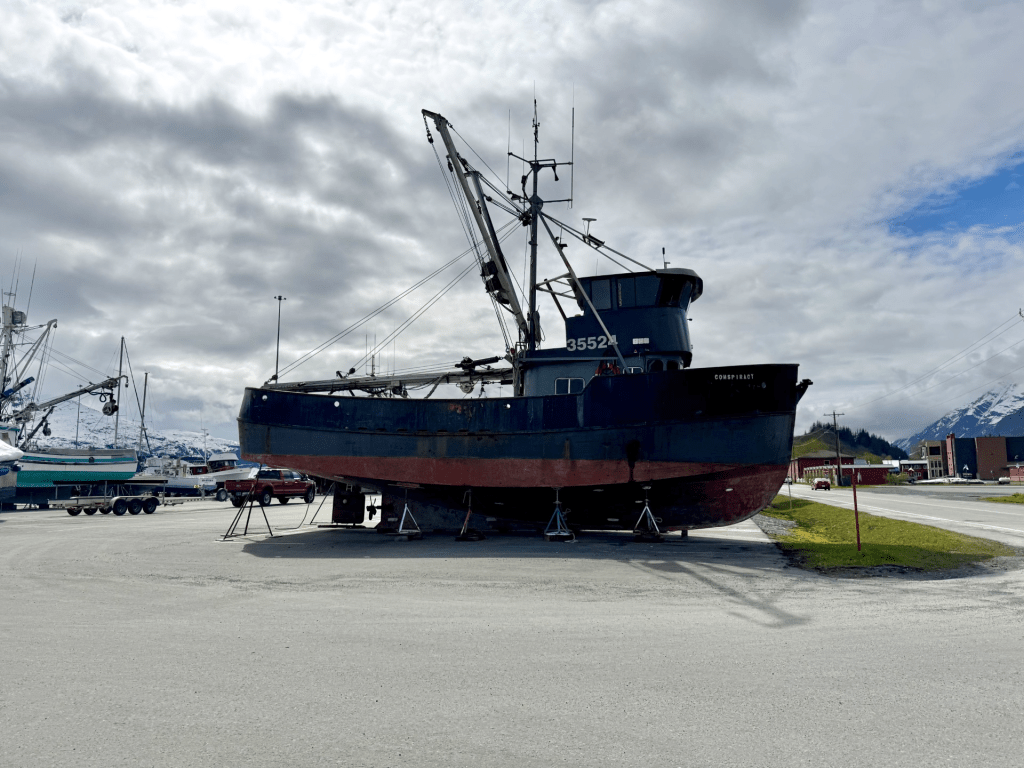

Valdez is, of course, also a fishing port and an excellent place for wildlife viewing. There is an abundance of waterfowl, bear (mostly black), birds of prey, otters, and other marine life.

Below: wildlife around Valdez and Prince William Sound

Above: black bear in town having a grassy snack

Above from top to bottom: a tanker in the distance with a grey whale with calf in the foreground; and tufted puffins in the Prince William Sound just outside of the Valdez Arm

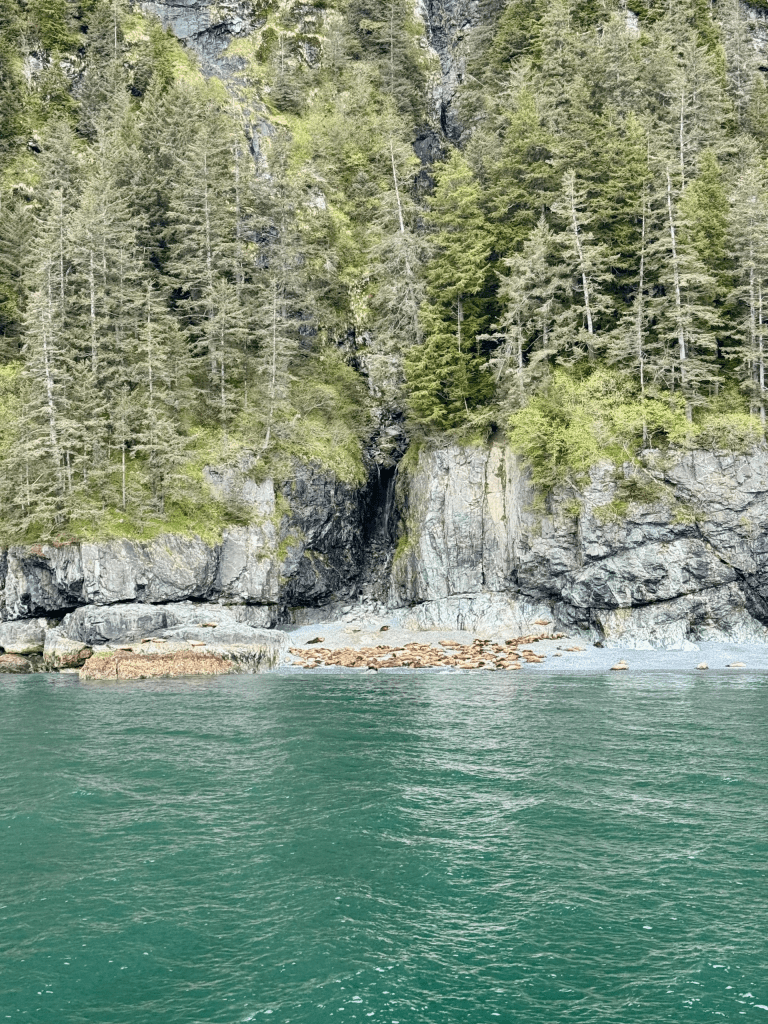

Above and below: Stellar sealion haulout on the coast of the Prince William Sound just outside of Valdez; see prior post from “Old Harbor, Kodiak” in this blog for more about sealions

Wildlife Corner

Perhaps the cutest of all the marine sea life, the sea otter (Enhydra lutris kenyoni), is found in abundance in the waters surrounding Valdez. Sea otters are the largest aquatic members of the weasel family and are playful, adorable creatures that are frequently found in pairs or groups (called a raft), floating on their backs and even wrapped in kelp to help them anchor. They live in the shallow waters of the Northern Pacific Ocean/Gulf of Alaska, only coming ashore occasionally with short, rigid front toes and webbed feet that make then well equipped for swimming. Although they come ashore, they are not good at land locomotion and are, in general, clumsy on land.

Sea otters are playful and social animals and frequently travel and rest in groups staying close to one another. There have been otter rafts seen with over 1,000 individuals in a single area. They are known not to migrate long distances with a home range of only several to 40 square miles.

Like many other species, the breeding males are defensive and territorial and will drive out other males who pose a threat to their breeding. Nonbreeding males usually remain in their own groups outside of breeding territories. Females reach sexual maturity between 2 and 5 years, with males at 4 to 6 years. They breed throughout the year with Alaskan pups being born in late Spring. They give birth to one pup at a time that are on average 3 to 5 pounds at birth and ride on their mother’s chest as she swims on her back. Females only leave their pups to dive for food and they are weaned by 3 to 6 months old at which time they are already 30 pounds. These little creatures can grow to 5 feet long, with males weighing 80-100 pounds and females 50-70 pounds.

Sea otters rely on their high metabolism and their plush coats to keep warm. The fur of sea otters is dense and provides insulation from the cold water temperatures, as they have no blubber for insulation. They have the densest coat of any mammal with 800,000 to 1 million hairs per square inch! Compare that to the average human with 200,000 hairs on their entire head. Their dense undercoats trap air providing insulation and they spend quite a bit of time grooming to remove salt crystals and oil to maintain it – if it becomes oily or matted, they can loose this air trapping mechanism and become hypothermic. This grooming also fluffs their fur resulting in further air trapping and the provision of warmth. This trapped air serves to provide 4 times the insulation as blubber would if it were the same thickness.

In order to maintain its body weight, a sea otter must eat 25% of its body weight per day. They forage in relatively shallow coastal waters and dive to the bottom to catch their prey and surface to eat their food. The dives generally last 1–2 minutes, but they can hold their breath for over 5 minutes. Dive depths range from 5 to 250 feet. Upon surfacing, the otter will roll onto its back and place the food on their chests. They have voracious appetites resulting in reduced numbers of prey species such as urchins in a given. They are well adept at utilizing rocks and shells as tools to crack and break open shells of the food they consume. They frequently have a “favorite rock” or tool that they keep stored in a loose flap of skin beneath their forearms (their “armpit”) in their for this purpose. They eat using their front paws and will use tools, such as rocks, to crack open shells. Their main prey species include sea urchins, crabs, clams, mussels, octopus, fish, and other marine invertebrates. Sea otter teeth are adapted for crushing hard-shelled invertebrates such as clams, urchins, and crabs. The sea otter’s main predator are killer whales.

Pioneer Field: PACD

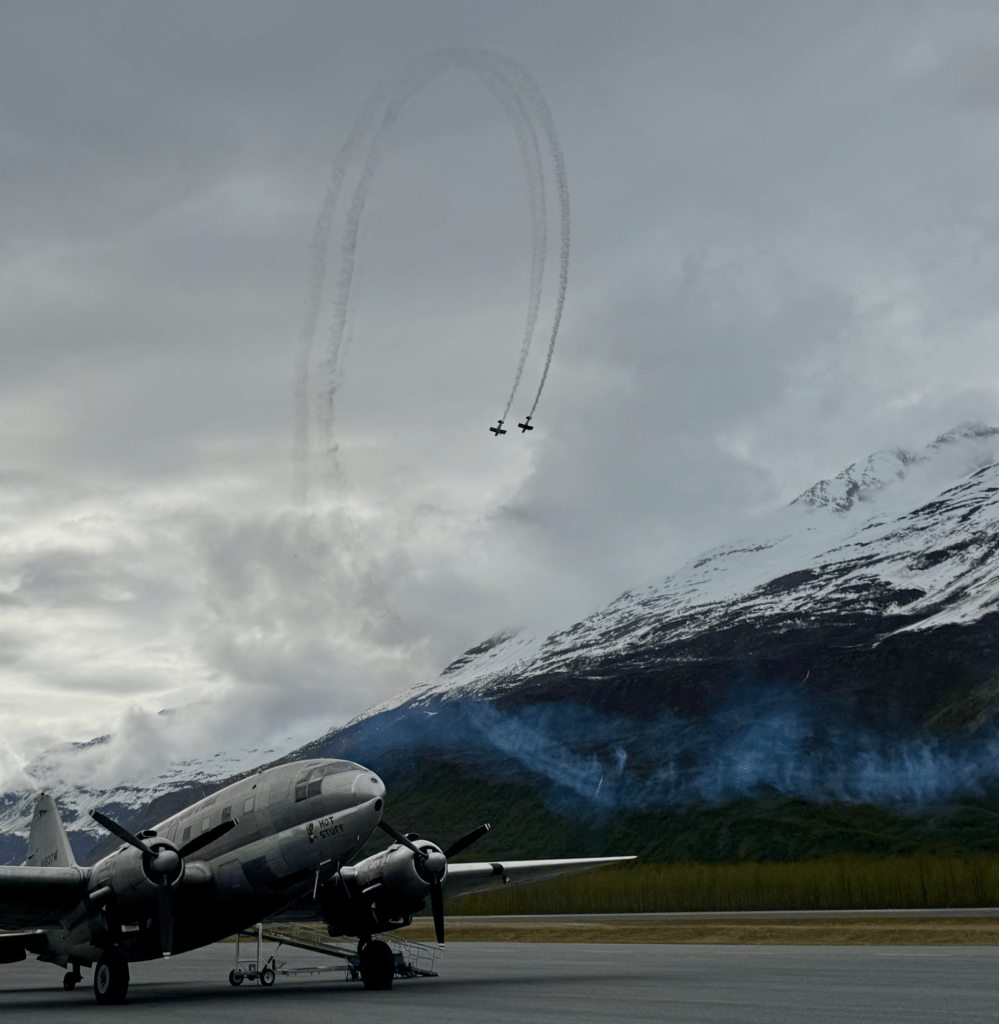

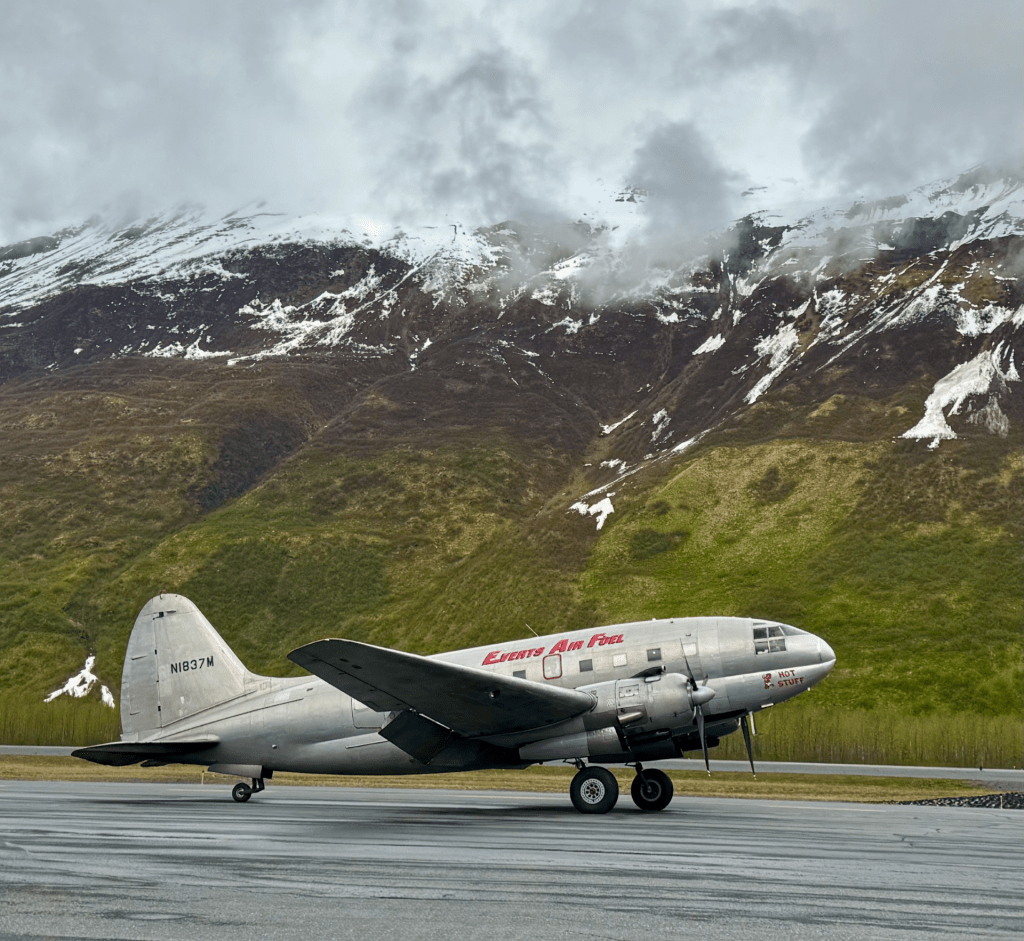

The Valdez airport (PACD), or Pioneer Field, has a paved 6,500′ x 150′ runway, sits at the base of beautiful mountains of the Chugach range, and is the only airport in town. It hosts the annual short takeoff and landing (STOL) competition and airshow with stunning backdrops of mountains and wildlife.

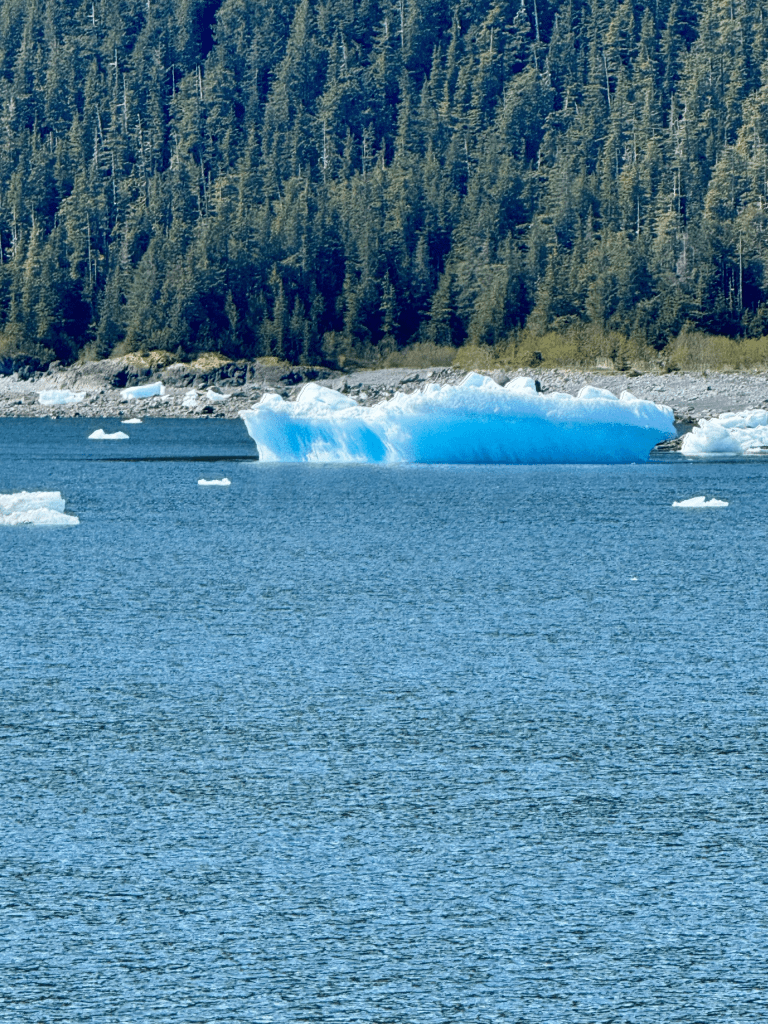

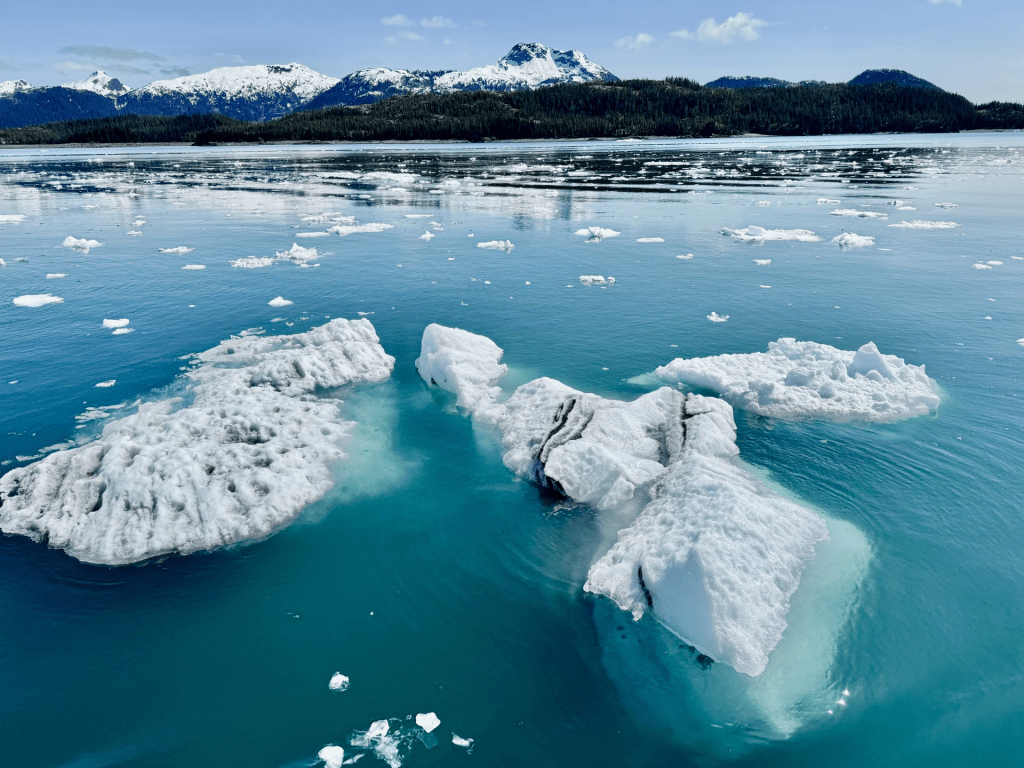

Below: Glacial ice calved from Columbia Glacier just outside of Valdez

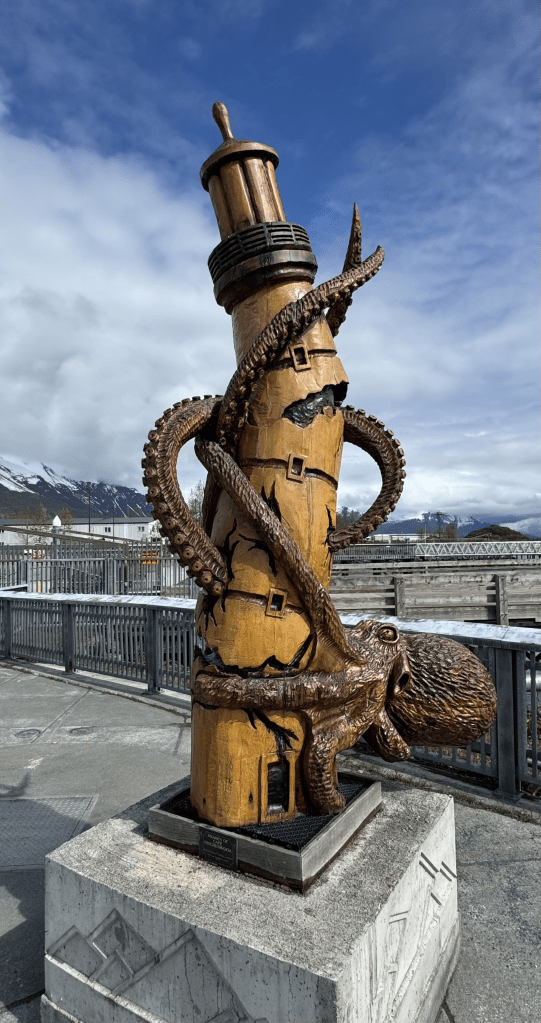

Below: Some neat carvings around the Valdez harbor

Leave a comment